Well, here we go again!

No, I’m not talking about election season – though with the presidential debate two weeks ago, it felt like the circus came to town.

Having grown up in the eastern United States, fall has become my favorite season. Christmas may be called ‘the most wonderful time of the year,’ but few things do I love better than watching tinges of foliage burst into vibrant display as the air becomes crisp and apple orchards ripen for picking.

But this year, ‘color’ takes on a different metaphor. Back in the spring, as social unrest grew in the wake of George Floyd’s death, confrontation of racism stole the spotlight from COVID-19, election coverage, and just about every other topic in the news.

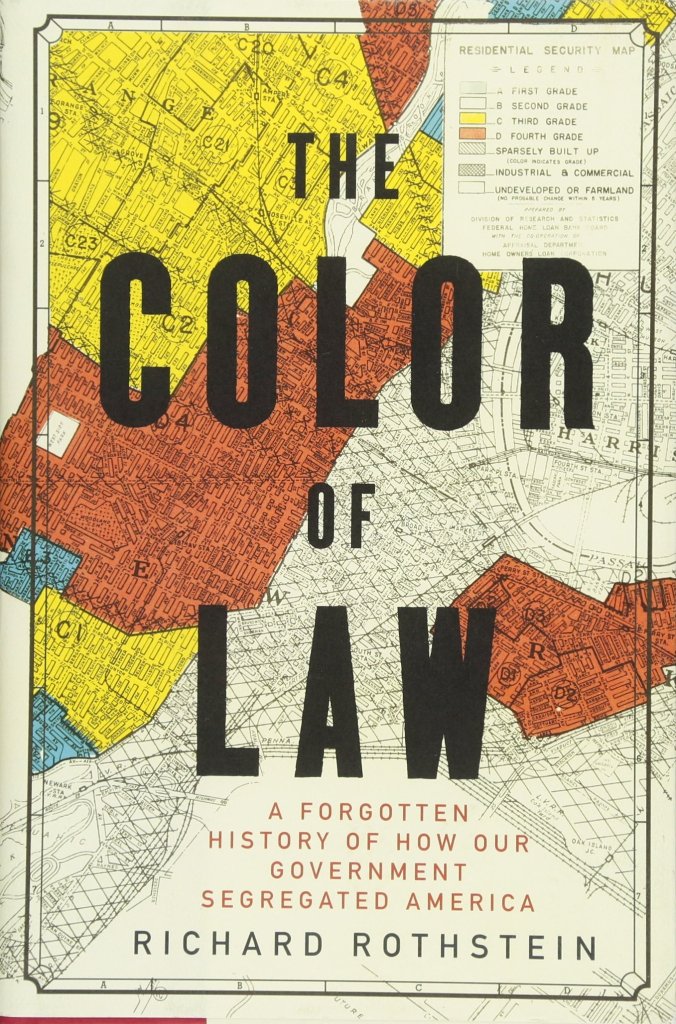

Likewise, I put my plans tackle The Brothers Karamazov on hold as I came across Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law.

But what compelled me wasn’t just timeliness. Rothstein introduced me to a critical conversation most of us have missed: “a forgotten history of how the United States government segregated our country.”

Before I go on, an acknowledgment: our government is filled with hard-working citizens who treat all individuals with respect. My father, who retired in January after forty years of service with the USDA, admonished me not to dismiss working for the government because of its problems. “The government needs good people,” he’d say. And he was right. If all the good people leave, who’s left?

That said, for all the things our government may do right, there’s plenty it’s done wrong. After commenting in my previous post that I don’t read horror stories, The Color of Law presented a nightmare:

“Racial segregation in housing was not merely a project of southerners in the former slave-holding Confederacy. It was a nationwide project of the federal government in the twentieth century designed and implemented by its most liberal leaders. Our system of official segregation was not the result of a single law that consigned African Americans to designated neighborhoods. Rather, scores of racially explicit laws, regulations, and government practices combined to create a nationwide system of urban ghettos, surrounded by white suburbs. Private discrimination also played a role, but it would have been considerably less effective had it not been embraced and reinforced by government.“

Yes, even venerated leaders like President FDR were complicit either in upholding racist policies, or turning a blind eye at their enforcement. Those who are aware of the government’s role in segregation have likely heard of redlining, blockbusting, and their subsequent result: white flight.

“Blockbusting, the subsequent loss of home values when speculators caused panic, the subsequent deterioration of neighborhood quality when African Americans were forced to pay excessive prices for housing, the resulting identification of African Americans with slum conditions, and the resulting white flight to escape the possibility of those conditions all had their basis in federal government policy. Blockbusting could only work because the Federal Housing Administration made certain the African Americans had few alternative neighborhoods where they could purchase homes at fair market values.“

In other words, realtors stoked objection to African-American neighbors based on fear — and federal law helped them get away with it.

Several decades before Rothstein, another writer recognized how the treatment of African-Americans was distorted by stereotypes put forward by mass media. During a career that included posts as Secretary of Education and Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, William J. Bennett observed the rise of two related phenomena:

“We are witnessing the emergence of a new ‘invisible man’ (the title of Ralph Ellison’s classic novel) in American society. This new ‘invisible man’ is the black inner-city citizen who doesn’t ‘do’ drugs.’ In fact, significant numbers of inner-city residents do not commit themselves to the drug world. Most blacks in our inner cities are law-abiding citizens who lead decent lives and disdain drugs; they are victims, not perpetrators, of drug crimes. Americans need to see that because, unfortunately, these citizens are almost invisible so far as much of public opinion is concerned. In the place of the law-abiding black man and woman we have seen the emergence of a new, all too ‘visible man’ – the black predator, the young inner-city black male who terrorizes communities, preys on innocent victims, or is arrested in drug busts. The image of the ‘visible man’ is given wide currency through the camera lens. Film report after film report sears images in our sensibilities: drugs, violence, the inner city, and blacks. These images and associations perpetuate a racial stereotype. We need to confront it immediately, before this myth and these images harden into dogma.“

Reading Bennett’s words, I thought immediately of nightly news reports I encountered growing up. My family lived in a rural area, but one of our local news affiliates was based in Rochester, New York. Crime reports typically featured young black men, and without a larger frame of reference, I experienced the association Bennett warned against.

Just as stereotypes form over time, we didn’t arrive here overnight. As Rothstein lays out in one heartbreaking example after another, decades of policy formation and enforcement privileged certain groups over others, leading to much of the socioeconomic disparity we see today. Property and prosperity are often connected; where you live affects every other area of your life. It’s hard to thrive if you’re merely trying to survive.

Bennett argues that the “best way to treat people is as if their skin color did not make a difference.” That doesn’t mean we ignore it; rather, we treat others humanely regardless of their appearance. If we had lived that way from the beginning, we might not be in the mess we’re in now.

And yet, as Rothstein concludes,

“This is not a book about whites as actors and blacks as victims. As citizens in this democracy, we—all of us, white, black Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and others–bear a collective responsibility to enforce our Constitution and to rectify past violations whose effects endure. Few of us may be the direct descendants of those who perpetuated a segregated system or those who were its most exploited victims. African Americans cannot await rectification of past wrongs as a gift, and white Americans collectively do not owe it to African Americans to rectify them. We, all of us, owe this to ourselves. As American citizens, whatever routes we or our particular ancestors took to get to this point, we’re all in this together now.”

Words to live by, no matter what season we’re in.